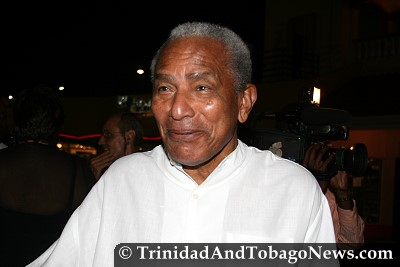

'Desi' Allum: patriarch and patriot

Desmond Allum

By Raffique Shah

June 20, 2010

My mother takes a seat in the limited space available in court. It is early June, 1970, and the preliminary inquiry into the charge of treason gets underway. She looks at her 24-year-old son sitting in the dock alongside 60-odd soldiers. A stern-looking Magistrate Roopchandsingh sits on the Bench, and Attorney General Karl Hudson-Phillips leads a formidable, impressive-looking prosecution team. Like other parents and families of the accused, she is nervous, worried.

When my name is called, young Desmond Allum rises to his feet and declares he is my counsel. His lawyer's robe is torn in several places. His voice is barely audible. He looks and sounds tame when compared with a confident Karl. My mother mutters to herself: 'Array baap! What kind of lawyer they get for my son?' Now she is more worried than ever.

In a matter of weeks, though, her respect for 'Desi' would grow. By the time the first court martial got underway in October, the 'second string' team of defence lawyers who stood with the 13 accused had grown in stature. Algernon 'Pope' Wharton, QC, Dr Aeneas Wills and Valerie Alcala, who defended Mike Bazie, were well-established in legal circles. But Desi, Allan Alexander (appearing for Rex Lassalle), solicitor Lennox Pierre, Frank Solomon, Vernon de Lima, Clem Razack, Clive Phelps and others were virtual unknowns before that six-month trial that gripped the nation's attention.

When the dust settled, a new breed of lawyers had firmly established themselves and all but changed the parameters of the profession. I focus today on Desi (and Allan, to a lesser degree) because of his passing last Thursday. These lawyers did not see us, the accused, as mere clients. They identified with what we stood for. They worked closely with us. Most of all, they sacrificed lucrative 'briefs' to work for months, with little financial rewards, for the 'people's soldiers' as we came to be known. Some day proper tribute will be paid to all of them.

But back to Desi: Many people were unaware that he had already earned his spurs, in a manner of speaking, in a race case in London, while he was a law student. He and George Hislop, one studying law, the other physical education, were arrested and charged by a racist policeman for 'attempting to steal motor vehicles'. George and Desi were merely 'liming' when the racist cop pounced on them. They refused to be intimidated by the policeman or the court, and eventually won their cases and their counter-charges for unlawful arrest. They were each awarded £4,000.

By the time the events of 1970 unfolded, Desi and Allan could easily work with Rex and me, headstrong though we were. We grew to respect each other from early on. We saw the court martial as a legal facade to what was a political trial, and we decided to politicise it even more. It was in those circumstances Rex and I, while studying our military law books in our cell, came across a peculiar defence: condonation.

This law held that if a soldier committed an offence and it was condoned by his commanding officer, he could not be charged with the offence. The catch was once one relied on that plea, one all but conceded that one had committed an offence-in this case mutiny.

Other lawyers might have advised against going down that dangerous path. Desi and Allan didn't. They were legal iconoclasts. I was the first to make that plea, stunning the court when Desi put me on the witness stand. Rex and Maurice Noray followed, taking the same route.

The court martial predictably dismissed our pleas, and later imposed some heavy jail terms on our backsides. But Desi, Allan and others did not give up. They took the dismissal of the condonation pleas to the Appeal Court, which unanimously ruled in our favour. The State appealed that decision, taking the matter to the Privy Council: we won again, and brought all our men out of prison, thanks to Desi and others.

Desi played a critical role in that trial. His cool, clinical cross-examination of witnesses was courtroom theatre. His plea of mitigation on my behalf was a classic that would later appear in print. Post-prison, we remained friends based on that bond that we forged in those crucial 27 months while I was imprisoned. Indeed, although he represented me, all of the accused soldiers saw him as someone who championed our cause.

Although we did not see each other frequently afterwards, we bonded whenever we met or phoned each other. I followed his illustrious career, as, I'm sure, he did my chequered life. I was pained when he called to give me news of his diagnosis. I frantically tried to see if anything could be done to save this friend I so respected.

But his benign outward appearance camouflaged a warrior. Desi had already decided he was not about to fight the inevitable, his mortality. That took tremendous courage. In life, he touched so many persons. As the end drew nigh, he won even more respect as he spoke out for justice in his beloved country.

I extend my sincere condolences to his wife Cathy and his family. You have lost a patriarch. The country has lost a patriot.

Share your views here...